Introduction to host modulation

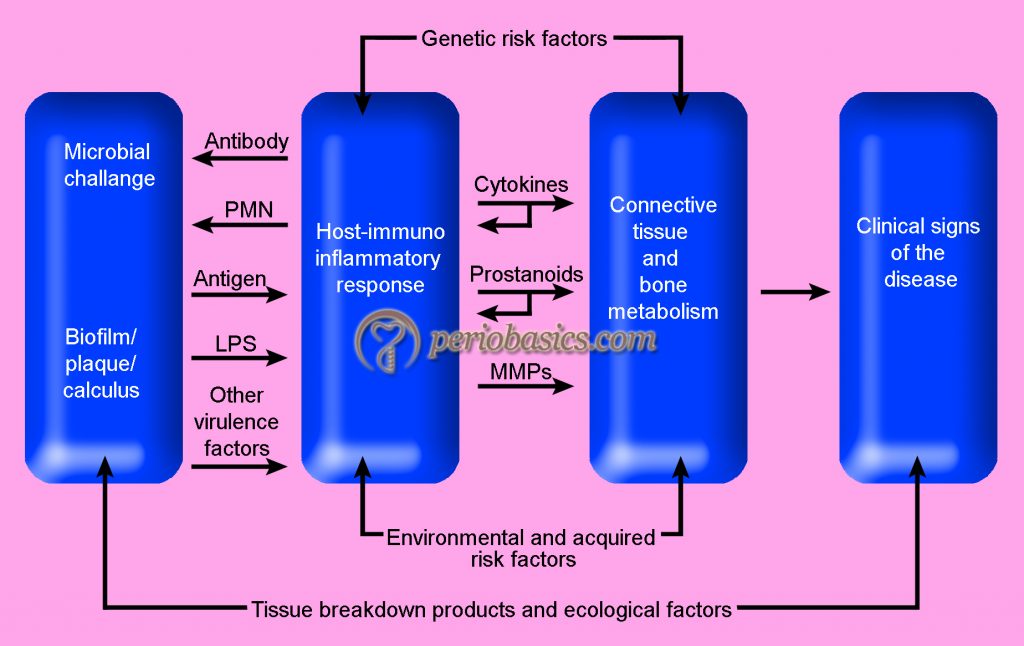

As discussed in previous chapters, periodontal disease progression is associated with subgingival bacterial colonization and biofilm formation. This microbial biofilm elicits a host response, with resultant osseous and soft tissue destruction. In response to endotoxins derived from periodontal pathogens, various inflammatory chemical mediators are released by the host cells. The immunoinflammatory response has been described as a ”double-edged sword”, and besides providing specific antibodies and polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs), that represent the dominant natural factors responsible for control of the bacterial challenge, it initiates the destruction of the connective tissue 1. Page et al. (1997) 2, stated that periodontal destruction in periodontitis is the result of connective tissue-degrading mediators such as, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and inflammatory mediators (prostaglandins, interleukins) that occur as a part of the inflammatory response. There is a vital balance between pro and anti-inflammatory chemical mediators in healthy tissue. When the pro-inflammatory mediators increase, tissue destruction results. The purpose of host modulation therapy is to restore this balance.

Basic concept of host modulation

Host modulation is a therapy that is targeted at the host response. As already stated, the result of the host-bacterial interaction is the release of various inflammatory mediators that cause tissue destruction. Using various therapeutic agents that can downregulate or inhibit the production, activation or biological function of the pro-inflammatory mediators is the basic mechanism of action of host modulation therapy.

Definition of host modulation

The definition of the host from a medical dictionary reads ”the organism from which a parasite obtains its nourishment or in the transplantation of tissue, the individual who receives the graft”. The definition for the term modulation is ”the alteration of function or status of something in response to a stimulus or an altered chemical or physical environment” 3.

The inflammatory response in periodontal disease includes the activation of leukocytes, neutrophils, T-lymphocytes and plasma cells. Subsequently, various chemical mediators are released by these immune-competent cells, which along with providing a defense to the host also degrade the host connective tissue.

Our present understanding of the pathogenesis of periodontal diseases has led to the development of host modulation as a treatment strategy that can be used in addition to conventional treatment approaches. This therapy acts on the host part of the host-microbial interaction. Host response modulation refers to the downregulating destructive aspects of the host response so that; the deleterious effects of various inflammatory mediators on the host tissues are reduced.

Historical background of host modulation therapy (HMT)

Golub 4, 5 and William 6 are considered to be the pioneers in the field of HMT in periodontics. While working on diabetic rats, in which there is an excess of collagenase activity, they observed improvement in the gingival health of rats treated with a tetracycline. Since, they were working on germ-free rats and the gingival inflammation, therefore, could not have had a bacterial etiology, the investigators concluded that the improvement was most likely due to tetracycline mediated inhibition of the host-derived enzyme collagenase. Collage-nases are one of the MMPs that mediate connective tissue breakdown and play an important role in the pathogenesis of periodontal diseases. These findings founded the basis for host modulation therapy.

After the introduction of the host modulation therapy, various agents are currently being investigated for host modulation including NSAIDs, tetracyclines, chemically modified tetracycline, anti-cytokines agents (IL-1/TNF blockers), recombinant human IL-11, recombinant tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase, synthetic matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors and bisphosphonates. All of these agents aim at modulating specific component of disease pathogenesis, including regulation of arachidonic acid metabolites, excessive production of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), immune and inflammatory responses and bone metabolism.

Pathogenesis of periodontal disease progression

As already discussed in previous chapters, periodontitis is a complex disease in which disease expression involves intricate interactions of the biofilm with the host immunoinflammatory response and subsequent alterations in bone and connective tissue homeostasis 7-9. Periodontal diseases have a well-defined bacterial etiology. Along with that, the present data suggest that environmental factors, acquired risk factors, and genetic risk factors play an important role in the pathogenesis of periodontal diseases. Kornman (1999) 1 proposed a model of periodontal disease pathogenesis that explains how the host-parasite interactions takes place and lead to the disease progression.

As the oral cavity is an open cavity, a clean tooth surface is soon inhabited by various microorganisms present in the oral cavity (see “Dental plaque”). This is the initiation of plaque biofilm formation. If this biofilm is not disturbed or removed (mainly by toothbrushing), the biofilm matures within a few days and various periodontal pathogens which are primarily Gram negative, start accumulating in the biofilm. These periodontal pathogens can create an environment of dysbiosis in the biofilm which marks the initiation of periodontal diseases. These microorganisms produce a variety of microbial substances, including chemotactic factors such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS), microbial peptides, and other bacterial antigens, which diffuse across the junctional epithelium into the gingival connective tissues. The junctional and epithelial cells in the gingival sulcus are stimulated by these products to secrete various inflammatory mediators, with IL-8 playing a very important role during the initial phase of immune response. IL-8 is a powerful chemoattractant for PMNs which are the first line of defense. PMNs directly kill the bacteria by various mechanisms, including intracellular mechanisms (i.e., after phagocytosis of bacteria in membrane-bound structures inside the cell) and extracellular mechanisms (i.e., by release of PMN enzymes and oxygen radicals outside the cell) (see “Role of neutrophils in host-microbial interctions”).

As the bacterial products enter the connective tissue and circulation, committed lymphocytes return to the site of infection, and B lymphocytes get transformed into plasma cells, which produce antibodies against specific bacterial antigens. As the lesion becomes established other arms of immunity such as complement system and phagocytic cells, etc. also participate in the host-microbial interactions. The inflammatory cells present in the battlefield secrete various chemical mediators such as interleukins (e.g., IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), prostaglandins (e.g., prostaglandin E2 [PGE2]) and MMPs 10, 11. These all products derived from the host cells are involved in the destruction of the connective tissue. Thus, if we can reduce the activity of these mediators, tissue destruction can be minimized, which is the basis of host modulation therapy. This therapy can be used to interrupt the positive-feedback loops and ultimately reduce the excessive levels of cytokines, prostanoids, and enzymes that result in tissue destruction.

Rationale behind host modulation therapy

HMT is directed on the host side of the host-microbial interactions. It is clear from the present evidence that host response is responsible for most of the tissue breakdown during the host-microbial interactions. HMT provides us the opportunity to modify the host immune response in such a way that tissue destruction is minimized. However, it must be emphasized here that HMT doses not stops the normal defense mechanisms, but instead, it amends the excessively elevated pro-inflammatory mediators to enhance the opportunities for wound healing.

Furthermore, it should be remembered that mechanical plaque control remains the primary focus for successful periodontal treatment; whereas, HMT is only recommended as an adjunct to conventional therapy for better clinical outcome. Also, the modification of risk factors either modifiable (e.g. smoking, uncontrolled diabetes) or non-modifiable (e.g. genetics, gender etc) plays a pro-vital role in successful treatment.

When to give host modulation therapy

As we know that bacterial challenge is the primary etiological factor in the development and progression of periodontitis. Many studies have clearly demonstrated that reduction in microbial load leads to the reduction in inflammation in periodontal tissues. But, many patients do not respond appropriately to the conventional periodontal therapy and the periodontal tissue breakdown continues. Present data strongly suggest that an abnormal immune response, genetic factors, environmental factors and patient’s systemic condition are responsible for the degree and magnitude of periodontal destruction. Studies have demonstrated that patients with generalized aggressive periodontitis have an excessive immunoinflammatory response 12, 13. Patients suffering from insulin-dependent diabetes have been shown to have high gingival crevicular fluid levels of PGE2 and IL-1β even in periodontal sites with minimal inflammation 14. IL-1β polymorphism is an important factor that contributes to the abnormal immune response in certain individuals.

So, it becomes clear from the above description that individuals who are at a high risk of development of severe periodontitis, should be given host modulation therapy. These include smokers, diabetics, and those who are positive for the IL-1 genotype.

Host response therapeutics for periodontal diseases

Various agents which can modulate the host immune response have been introduced and tested for their efficacy. These agents may modulate the immune response by a variety of mechanisms. These include prostaglandin inhibitors, cytokine inhibitors, MMP’s inhibitors and bone resorption inhibitors. A detailed description of these agents has been given in the next article.

Conclusion

Host modulation therapy has become an important modality of treatment for periodontal diseases. However, this therapy is an adjunct to the conventional periodontal treatment. Furthermore, this therapy is not indicated in all the patients and should be used after a thorough evaluation of the patient. In the next article “Host-response therapeutics for periodontal diseases” we shall read in detail regarding various therapeutic modalities used in HMT.

References

References are available in the hard-copy of the website.